In the early 1980s, George Legrady was in Harold Cohen's studio at UC San Diego—working alongside AARON, one of the first autonomous art-making systems ever built. Four decades later, his work inhabits the permanent collections of the Centre Pompidou, Whitney Museum, SFMOMA, LACMA, and the Smithsonian. Yet until now, Legrady has never released his digitally native works as digital art.

Digital Giverny changes that. Created in 2018, just three years after the Neural Style Transfer algorithm was published, these fifteen unique works exist in visual territory no human hand could reach alone: Monet's legendary gardens fused with rusted industrial decay, processed through a system that finds harmonies human perception would never propose but instantly recognizes as beautiful.

We spoke with Legrady about his unique trajectory through computational art, creating using early Neural Style Transfer, and what it means to finally release natively digital work to digital collectors.

AM: You trained in Harold Cohen's studio in the early 1980s, working alongside AARON—one of the first AI art systems ever created. How did you end up there, what drew you to this frontier so early?

GL: My meeting with Harold happened through pure chance circumstances. I had moved to San Diego in August 1981 and briefly stayed with an artist friend, whose partner, Jeff Greenberg, turned out to be Harold's studio assistant. My artistic work at the time focused on a conceptual approach to photography—in particular, I was doing staged photographs, meaning assembling scenes in the studio in front of the camera as a way to explore the semiotic aspects of photography.

A few months prior to the move, in response to a commission, I had produced a two-page spread for the Canadian art journal Parachute titled "Artificial Intelligence." The artwork consisted of two photographs of a tabletop scene where a set of objects got moved around between the two scenes. Underneath the images, a set of questions and answers simulating MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum's famous ELIZA computer-generated conversation. The goal of the text in my layout was to allude to what colors viewers might have guessed the objects in the black and white photographs had.

Jeff must have shown this to Harold, and once we were introduced at a casual social gathering, Harold generously invited me, giving me access to his mainframe PDP-11 computer in his studio at UC San Diego. This was a unique and unusual opportunity as access to computers was difficult to get, and I may have been one of very few individuals to be given such access to Harold's system.

"Over the period of a few years, I learned C programming on his system and produced one work titled 'Perfume,' dated June 17, 1982. This evaporation process, titled diffusion, is what current generative AI image synthesis algorithms are modeled on."

Over the period of a few years, I learned C programming on his system and produced one work titled "Perfume." I recently discovered the printout in my storage space. It is dated June 17, 1982. The concept of the animation was to visualize how perfume molecules, when escaping from a semi-enclosed space like an open bottle, proceed to evenly distribute themselves within the larger surrounding space. This evaporation process, titled diffusion, is what current generative AI image synthesis algorithms are modeled on.

AM: Cohen famously built software to simulate his own decision-making process. Did that framework, the artist encoding their own aesthetic logic into a system, shape how you approach collaboration with algorithms today?

GL: One of the things I learned spending time in Harold's studio was his inquiry: to examine how his implicit procedures by which he created a painting could be described through language, and once described through language, could then be turned into a set of rules by which software could produce a result—and then to measure to what degree the outcome could advance Harold's ideas about how images are created and how they work. This approach shifts the conversation from technological innovation towards more philosophical inquiry about how we can imagine technologies serving questions about how we perceive and exist in the world.

AM: Your career reads like a timeline of computational art history: database narratives in the '90s, natural language processing in the 2000s, machine learning visualization before the term was common. Yet throughout this, your primary relationship has been with traditional institutions—museums, galleries, permanent collections. How have you navigated being a computational pioneer while existing within a system that largely sells physical objects?

GL: My photographic artistic practice centered on what back then was considered the alternative scene, meaning exhibition and publication venues that functioned outside of the commercial fine art gallery sector. I quickly realized that the works I was producing were more research-based and informed by critical inquiry, rather than catering to market interests.

I was able to gain employment in art schools and academic institutions, which allowed me to have an income and at the same time continue my explorations. This approach informed my new methodology as I transitioned to computing. Additionally, such conceptual works were not easy to introduce within a commercial art market, so I actually focused on exhibiting in either alternative spaces or in museums—primarily in Europe—that did have budgets to fund the creation and exhibiting of digital artworks.

"I quickly realized that the works I was producing were more research-based and informed by critical inquiry, rather than catering to market interests."

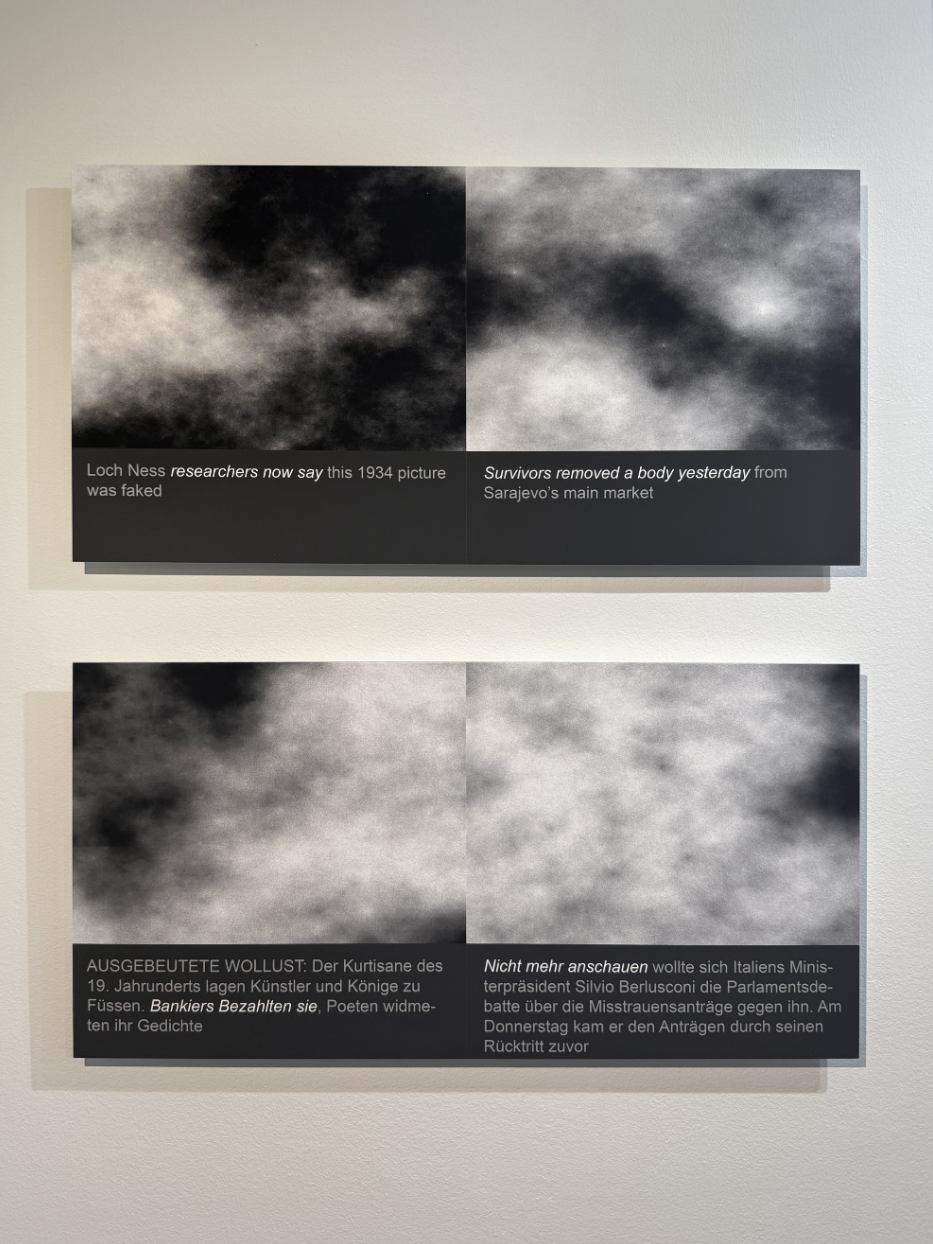

AM: Digital Giverny merges photographs from Monet's gardens with images of rusted industrial surfaces—organic and mechanical fused through an algorithm that finds harmonies human perception may never propose. What drew you to these two sources, and what were you searching for in their collision?

GL: I was always attracted to industrial spaces or construction sites as they were in-between spaces, partially chaotic, and on their way to transitioning to something else. I visited Giverny in 2017 and took a lot of photographs of the gardens. It must have been late fall as the flowers and plants were slowly disintegrating.

I come out of a photographic tradition which explored the formal construction of images, and the goal in my case was to create images with complex textures that bordered on the balance between chaos and order. My Master of Fine Arts project at the San Francisco Art Institute was titled "Urban Nature." The works consisted of black and white 35mm still photographs that explored the contrast of forms, intersecting natural elements with man-made objects and locations.

Back to the present: I found the photographs I took of rust surfaces in Santa Barbara to be beautiful, but I wanted to transform them in some way. The idea of taking the Giverny nature scenes and embedding them with the rust industrial surfaces became a way to hybridize nature and culture.

AM: You created these works in 2018, when Neural Style Transfer was still relatively new—just three years after the algorithm was published. Can you walk us through your process? How much control did you exercise versus allowing the system to generate with its own internal logic?

GL: I direct a graduate research lab at the University of California, Santa Barbara that is dedicated to the study of the impact of computation on visualization. My department is in the unusual and interesting situation of belonging to both the College of Engineering and the College of Humanities / Fine Arts, so our practice and research aim to realize hybrid arts-engineering projects that could not be achieved in either department on their own.

I am an artist, but many of my graduate students come from Engineering and Computer Science, so there is this amazing opportunity to engage with current technological processes that my students bring to the discussion—processes that I could not have identified and implemented on my own.

So I do studies with my students, and we experiment with algorithms to see to what degree we can arrive at results that the students can present as papers at engineering conferences, and that I can integrate into artistically-informed projects.

"We are interested in pushing the boundaries and arriving at results that may not have been the intention of the invention—as a way to arrive at new discoveries, both technical and aesthetic."

Style Transfer utilizes convolutional neural networks, which we had explored some years earlier as a way to process photographic images. I have always understood the photographic image as a machine-generated process, so I am highly aware as to what degree of influence I may have on what the machine can produce. We are interested in pushing the boundaries and arriving at results that may not have been the intention of the invention—as a way to arrive at new discoveries, both technical and aesthetic.

Style Transfer functions by imposing the stylistic features of one image onto the content of another. In our implementation, we weighted the system toward the flat rust panels, allowing only limited detail from the Giverny photographs to remain legible. Due to computational constraints, both image sets were initially scaled down; once the desired tonal textures emerged, the results were scaled back to full resolution, and the rust images were layered to reintroduce surface detail. This is why screws and metal folds remain visible. In some works, traces of the Giverny source persist—most notably in Coral Veil, where the iconic bridge appears faintly in green.

AM: Style Transfer was a conceptual breakthrough that enabled so much to follow—GANs, diffusion models, the AI image generators now ubiquitous across culture. As someone who was working with the algorithm at the very beginning, how do you view the explosion of AI-generated imagery since then? Does it change how you see Digital Giverny's place in that history?

GL: I have been engaged with computational explorations since the early 1980s, prior to digital imaging, time-based sampling, the internet, artificial neural networks, and so on. It's been an ongoing and highly engaged conversation with each new technology that enters the scene. My goal has been to explore to what degree the new technologies open a previously unimagined conceptual space that can lead to aesthetic explorations.

An exhibition titled "The World Through AI," recently presented at the Jeu de Paume museum in Paris and curated by Antonio Somaini, featured current AI-based artworks selected on the basis of their contributions to philosophical reflection and cultural critique—addressing the question: what does it mean that we are in this simulated, technologically defined space, and how do we imagine ourselves in such a world? My work was included in the historical section.

"I have been engaged with computational explorations since the early 1980s, prior to digital imaging, time-based sampling, the internet, artificial neural networks, and so on."

Equivalents II was created in the early 1990s, and its contribution to the conversation was that it may be the first software-based artwork that asked the public to provide a text prompt, which was then parsed by our custom software for parameters used to set values to create an abstract composition. Each phrase produced a unique composition. At that time, there was no one to talk to, no one to discuss to what degree that software fulfilled conceptual and aesthetic goals.

Style Transfer is a technique that reimagines existing images through an aesthetic modeling process. By contrast, current generative AI image synthesis systems invent images from text descriptions, relying on statistical analysis across billions of labeled images. While both approaches are computational, they operate through fundamentally different procedures. With Digital Giverny, my intent was to explore the extent to which an aesthetic outcome could emerge from the fusion of two distinct subject matters: garden imagery and industrial surfaces.

AM: Your work has been collected by the Pompidou, the Whitney, SFMOMA, the Smithsonian—institutions that define contemporary art. Yet these works have always been translated into physical form for those contexts. Why release Digital Giverny as natively digital, collectible on-chain, after keeping this work in your personal collection for eight years?

GL: As an image maker, I had to wait from 1981 to around 1985 to be able to create "born-digital" photographic-looking images once the technology became available. The shift from physical to digital was transitional, and a tremendous shift in many ways. I gave up my chemical-based photo darkroom in 1988 and never turned back.

Much of the work I did a few decades ago was in fact not physical but digital data-based—organizing data into what I called "archives," collecting data from the public in museum settings, processing the data and presenting the results through cinematic projections. No matter to what degree my works may have since then been given physical, material form such as works-on-paper, lenticular panels, or tapestries, they are fundamentally digital in substance.

"One can consider the software as the authored artwork, and the digital results as the expression of the software's agency."

I should add that the digital outcomes are in fact the results of custom software, so one can consider the software as the authored artwork, and the digital results as the expression of the software's agency.

The Digital Giverny series exists at the crossroads of nature, technology, and information aesthetics—making it especially resonant for blockchain presentation. The project's emphasis on visual information poetics—the interplay of organic form with industrial surface—translates naturally into blockchain's own conceptual space of data structures, encoded identity, and distributed representation.

AM: What do you hope collectors—particularly those who have been building collections of computational and AI-generated art—understand about this body of work?

GL: Digital Giverny is a computational reinterpretation of Monet's gardens, using custom software and AI processes to explore how cultural memory and visual history are translated through algorithmic systems. The work is not conceived as a set of images alone, but as an authored software framework in which aesthetic decisions are embedded within code.

Presented on the blockchain, Digital Giverny emphasizes provenance, continuity, and authorship in computational art. Each work on-chain represents a manifestation of the system's operations, preserving the relationship between algorithm, image, and artistic intent. For collectors of generative and AI-based art, the project offers not novelty, but a durable, historically grounded approach to computational image-making—where the artwork exists as a living system rather than a static object.

"For collectors of generative and AI-based art, the project offers not novelty, but a durable, historically grounded approach to computational image-making—where the artwork exists as a living system rather than a static object."

Timeline: George Legrady's Artistic Practice

1972–1978: Documentary photography

1978–1984: Staged studio large format photography

1981: Acquired computer programming

1985–1990: Born-digital still photography

1992–1998: Interactive data, CD-ROMs

1998–2015: Interactive museum installations, data visualization

2011–2016: Photographic lenticulars

2016–present: Algorithm studies for still and animated visualizations

About Digital Giverny

Digital Giverny is a series of 15 unique artworks created in 2018. The collection releases January 19th, 2026, exclusively at automata.art. Each work is 0.5 ETH.